|

| My great-grandparents & family |

I write about my family history and culture. It has grown into a passion of mine.

Several essays of mine have been published in a local writing journal. For example, if you go to the Pennsylvania Writing and Literature Project's (PAWLP) ejournal 210 East Rosedale and flip to page 17, you will see my essay about an aunt: Cent'anni to a Family Gypsy.

Recently, I started a family blog, Homemade Ravioli, as a way to keep our family stories alive. I gave access to any family members who wish to share stories and photographs--hopefully more will join in as the months pass.

For the past two years, I have been producing a podcast, I Remember, where I interview people about their family history and heritage. Finding people to interview has been a challenge, but I prefer this brand and format to how I started--by sharing my stories. I hated my voice! I figured I would save my stories for writing and would use the podcast to sharpen my interview skills and to gain some experience with podcasting--since I want to be able to teach it to students.

For the past five years I have been writing and revising a YA novel honoring my family's Italian, turn-of-the-century roots. It isn't "about" my family in any way, but it gave me an opportunity to dig into lots of research about the region of southern Italy where we come from.

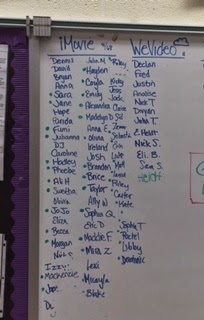

By asking my students to create a one to three-minute video podcast about their family history or culture, I got to teach several things: informational writing, context, interviewing, primary sources, digital composition, sound devices in writing...and passion.

For two weeks my kids see me passionate about something. As always, I write as they write. And I am genuinely interested in what they discover about their culture and heritage and history as much as I am excited about my own.

The Projects

I keep a YouTube playlist of the projects which you should be able to access right from this page. If you click on the "PLAYLIST" tab on the top left of the video screen, you will be able to scroll down to any of the videos published.

I can't tell you how many of our kids stopped me after classes to share little snippets of their time with mom, dad, grandmom, and grandpop--which never made it into these videos. The process of seeing these videos develop was truly special for me.

Finally, students learned that narrative, as Thomas Newkirk writes, "is the deep structure of all good sustained writing." When we struggle with textbooks it is typically because writers dispose of the narrative form. Yet, through this practical experience, we learned how narrative and anecdote can serve as "a frame for comprehension" for informative texts.