Abstract

"The Common Core" distracts educators away from a pressing need: training in digital literacy. Access to technology is access to power. Without training and resources education continues to drive a larger wedge between the haves and have-nots. With, at best, a casual mention of digital

literacy, the Common Core ensures only one thing—as the Digital Renaissance

evolves we are all at risk of being left behind.

What the Common Core Missed

As Digital Literacy provides access to information—and access to power—this

Digital Renaissance exposes the haves and the have-nots in our country. While education must always

remain pedagogy-driven, society’s immersion in technology can not be ignored by

educators. Without the correct

training and focus on a Common Core built on the needs of this society,

teachers will no longer be able to help students unlock

their futures.

Teachers need immersion and training in technology in order that

students may have immersion and training in technology. Technology passes books as the access

point to information and power. In a 2008 PEW study, researchers learned that the primary

source for research done at or for school is the internet: 94% of teens use the

internet at least occasionally to do research for school and nearly half (48%)

report doing so once a week or more often. Without a revised Common

Core, we are in danger of contributing to an even greater divide of haves and

have nots—and it isn’t all about having the money to supply the technology. Permitting a culture of teachers of

haves and have-nots is my greater fear—those who have the comfort, experience,

and training to immerse themselves and their classes in digital literacy and

those who simply have not.

Technology is largely taught in isolation. Computer rooms grow in our schools while other classrooms are lucky to house one or two

computers. This Sex Edification of

technology contributes to an educator’s fear or resistance. Rather than synthesize digital tools

with real-world applications and core curriculum, the digital tools sit on

tables like $1,000 encyclopedias or typewriters. Just like Sex Ed, we tend to believe "someone else will

teach it" and do so in isolation.

The fact is, we are online.

We are digital readers. We

are digital writers. All roads intersect and we have redefined Digital Reality

with people. Within the last

decade Digital Reality shifted from a game played on an LED battlefield to a

way of life. In many ways, we live

every moment of our lives in a digital reality because the world is

making more land—a digital landscape.

Yet instead of training educators, young and old, to engage inspiration

and inventiveness, American politics burns the digital landscape right from

under our feet, almost as fast as it can be created, with the oversights of the

Common Core.

The axiom good writing is good writing will never be displaced. Whether we teach with chalk, white

board markers, or Smartboards (which some will consider outdated by the way), the fundamental truths of reading, writing, and

arithmetic remain among the few constants in education, yet we stand on the

frontier of a Digital Revolution and the national plan is fragmented and

weak...actually, there is no plan. With only a too casual yawn

and nod at technology, the Common Core nudges educators to rewrite curriculum

built on international testing standards.

We can’t just leave using technology and digital literacy to the whim of

individual teachers—yet this is what the Common Core establishes.

Common Core Oversight #1: No

specific mention or acknowledgment of digital literacy

Without the appropriate level of

leadership and training, computer labs can best be labeled technology dumps as

educators are left to decide for themselves—depending on their school’s budget

and climate—how best to incorporate technology in the classroom. For what we do and produce in our

American classrooms, Underwoods, hardback encyclopedias, and tri-folds are

currently just as effective as computers—given two classes, one with technology

and one with typewriters, books, and cardboard, we would see little difference

in the products between the classes.

Until there is a common training

program and goal built on digital literacy, educators will continue to use new

technology in old ways because the old ways are rooted in the financial soil of

testing and achievement. What

message is reinforced when our schools receive Race to the Top funds and

selective waivers from the No Child Left Behind requirements all in the name of

carrying the torch for the Common Core?

What incentive exists to grow with the technology? How will we ever expect educators to

see new technology as anything other than a digital poster, encyclopedia, or

way to type and print?

In reality, we will fail our students

when it comes to digital literacy and this new access to power.

Education is failing—we are

failing to be led. We are failing

to be supported. We are failing to

be recognized for all that we achieve with technology in spite of the “you’ll

figure it out” model. Buttressed

by the financial obligations of Achieve, Inc., the ACT, and the College

Board, the Common Core supports

the testing business. Who is in

the business of supporting, leading, and recognizing educators? Who is in the

business of supporting and leading technology use in education? Educators. I assure you, we will figure it out. Yet, along the way, we fight district

by district for what we need, to overcome the inequities from school to school,

and only if we’re lucky and blessed some of us fight to bring American

education into the Digital Renaissance.

Common Core Oversight #2: Reading

The Common Core does little to

encourage adequate growth and progress of technology use in the K-5 Reading

Plan.

Listing no formal digital reading

expectations among its Foundational Skills, the Common Core mentions in its

Reading Standards that students should analyze how writing is affected by

different modes, particularly multimedia.

A modest, but promising start considering “multimedia” does not

explicitly mean digital.

Multimedia can mean photography, a poster, a set of slides. Depending on the whim, comfort, or

training of the teacher, an informed exposure to digital reading may never

occur for many students.

Additionally, and equally as

distressing, in the Common Core Reading Plan, from the 6th through 8th grades, students are asked to compare and contrast different

forms, including multimedia. Even if I imply “multimedia” as digital and

online, it does not mean others teachers will—education outgrows that word on a

daily basis.

Digital reading for citizens and

consumers in our society is a non-negotiable skill. It is a must-have. Perhaps

this dearth of digital reading is a reflection of the comfort level that our

Common Core designers have with the K-8 age range handling costly digital

hardware. Perhaps they have

well-founded fears of elementary and middle school students seeing pornography

or graphic violence on the internet.

Perhaps the focus in K-8 should be more on the skill of analysis than the

digital vehicle through which the analysis occurs. This is plausible until we consider the next phase in the

Common Core progression.

Sadly, from 9th-12th grade there are no digital (or multimedia) reading

expectations. There are no

expectations for students to interact with what they read digitally. There are no expectations to instruct

students in how to be a savvy digital reader and consumer. None. Zero. Digital

reading, disguised or misinterpreted as multimedia, ends at the 8th grade. In our Common Core, digital literacy may never develop for

some of our students.

Is this plan driven by pedagogy and

the needs of an emerging societal shift?

Or is it the architecture of a financially asphyxiated team regarding

education through test-colored lens?

Common Core Oversight #3: Writing

Heroically, the anchor standards for

writing in the Common Core ask students from the fourth grade through high

school graduation to “use technology, including the Internet, to produce and

publish writing and to interact and collaborate with others.”

The focus words are produce, publish,

interact, and collaborate—no explicit mention of achieving these things

digitally other than through use of the Internet. While the Internet is one important acre of the emerging digital

landscape it does not cover everything.

Suggesting Internet equals digital literacy is already an old-fashioned

understanding of technology; I’m reminded of Rupert Murdoch sounding out of

touch recently as he railed against Google as an Internet pirate. An illustration of just how confused

people in power can become; we so often mistake the size of someone’s bank

account for the breadth of one’s knowledge.

Educators are forced to imply the

word “digitally” within the expectations of the Common Core—but what happens

when that is not implied? The

problem with the language in the Common Core is that “digital” is implicit and

therefore this aspect of the Common Core is open to the vagaries of a teacher’s

digital comfort level.

For example, if I show my students a

sample of an essay (on the internet), and then students brain storm ideas face

to face while hunting for topic ideas (on the internet), then type a paper on a

laptop while checking my requirements for the assignment on our school website

(on the internet), then save the essay to the school server (on the internet)

and print it wirelessly in order that I might tack their essays across the

walls in my classroom, haven’t I then fulfilled the expectations of the Common

Core: produce, publish, interact, and collaborate? I included the internet and I can complete that assignment

in less than a week.

Fundamentally, I’d hope the Common

Core meant to express that our students also digitally produce, digitally

publish, digitally interact, and digitally collaborate. Embedded in what it means to be alive

in 2012, much of the world communicates through digital means—if we leave these

emerging digital tools to the next Angry Birds or just to keep in touch with family

and friends then we lose—and you can point your fingers right at us, the

American educators, because we will be working in a system which fails all of

us.

It is not too late for American

education to right itself and become active participants in the digital

literacy renaissance. We belittle

the tools of technology when we do not actively reach to train our teachers and

then our students to use them.

Otherwise, computers are little more than toys, typewriters,

encyclopedias, or delivery systems for web-based supplemental tools such as

Study Island (which provides little more than supplemental worksheets and

activities on-line). Technology in

education often suffers beneath the yoke of simply pulling the same lessons

built on the same expectations of tools-gone-by.

Why? Because that is all we know—it’s what we were raised

on. A computer works like a

typewriter, works like an encyclopedia, works like a tri-fold; therefore, that

is all I’ll expect of it.

It is no longer enough to put

computers in schools and roundly call it a success. Educators need training in digital literacy, but that takes

having a plan. Currently, teacher

training programs such as the National Writing Project are under the gun to

have its funding eradicated. If we

ever really want to see our young people grow into creators and innovators,

then we need teachers trained and constantly practicing and talking all aspects

of the art of teaching—added to this is the digital component all teachers need

training in digital literacy.

We seem to be working backwards—the

talk is that teacher training is a target of upcoming economic cuts and yet we

roll out a Common Core entrenched in testing. Write your Senators and Congressmen to take a long hard look

at the Common Core and then at the digital landscape. They won’t have to look far to see it—its inspiration is

burning all around them.

Common Core Oversight #4:

Assumption

Now there is a caveat for the Common

Core—intended as merely a guide it assumes that districts can add and modify as

they see fit. This is a big

assumption by our best and brightest.

Irrespective of neglect born from pedagogy or finance, we as educators

can’t in good conscience leave this emerging and critical skill to the hope and

discretion of “do as you see fit.”

Digital literacy skills are a must have for every child. We can’t assume that it will get

done. We can’t assume that

all kids have access to it at home—we have to demand training, resources, as

well as the leadership. We need to

demand a better plan—we can measure training. To the educational leadership, raise up your teachers,

expect more—and arm them with the tools to do more.

Today, the Common Core leaves our

young people digitally unarmed.

Students will file out of graduation and into a world milling and

seething with technology…and we will have barely touched on it unless a rogue

teacher exhibits the comfort and expertise to use it and teach with it.

The one thing that education should

have going for it is technology—the depth and quality of our nation’s education

should rise along with the continued evolution of technology. We’re in the infant stages of a Digital

Renaissance— and while our biggest and brightest sleep on this issue, we have a

professional responsibility as educators to make ourselves digitally

literate.

I also hold the mirror up to

myself. We need to take the

responsibility for the digital literacy that this generation will need to

thrive and survive not only in the workplace, but in the family unit. Digital literacy has infiltrated our

television screens, our smart phones, and in our daily moment to moment

communication with our family and friends—all of which sits in many of our

pockets or bags.

Digital literacy is about more than

recognizing the Twitter or Facebook icon at bottom of a commercial, it is

bigger than the fear of graphic imagery that our young people could be exposed

to on the internet. You know they

print pornography with paper and ink too, but that never stopped us from going

to the library, bookstore, or handing out paper and pencil. Avoid the luxury of excuses—make

yourself more digitally literate.

Common Core Oversight #5: All

Teachers Left Behind

Recently I wrote a grant for

technology so that my students could be digital writers and readers more

consistently and found myself presented with a concern that technology would

replace pencil and paper. The insinuation

slanted technology more towards fun or idle time and pencil and paper as the

emblem of diligence and getting our knuckles dirty with graphite. Every adult in education is responsible

for that perception.

Digital writing still requires that

writers move through the recursive phases of planning, reflecting, drafting,

and revising—the skill is still the skill, and, no, technology is not essential

to the core of that skill, but we can't simply bring only traditional mindsets

to current literacy practices. The

day is coming when reading and writing on paper will not be good enough in our

world. The definition and cultural

concept of a textbook is about to be exploded by Apple and its

competition. Digital

technology creates new skills and redefines old skills—life is about growth and

change. Depending on your

perspective I suppose it is also about withering and dying…and being left

behind.

I came across the anecdote that a

group of teachers, instructed on some advancements to school email, learned

students would also have their own school email accounts. A concerned teacher questioned why we

would give middle school kids this kind of access—how could we possibly trust

them? Can’t they abuse this? What about if one kid cyber bullies

another through the email we handed to them? The teacher leading the group retorted, “Why would we ever

trust them with pencil and paper?”

These concerns illustrate the

boogeymen that can be conjured without the proper exposure and training to just

what these tools are, what they can do, what they can’t do, and how they

improve education and our collective quality of life. It also demonstrates how far behind some of us are—eh,

Rupert?

If we allow the innovations of technology to serve merely as

distractions or vehicles of our social lives then that is all we are going to

get out of them.

Digital tools aren’t used in schools

because they are cute or the latest thing or a vehicle to produce a sexier

reproduction of a tried and true lesson, but they should be used because they,

and only they, address the specific and unique skills emerging in today’s

world.

We underwhelm ourselves sometimes.

Politicians, parents, and educators

need to share in a common core.

Our core should be built on the recognition that the digital age is here

and it is a renaissance that we need to engage. We can’t continue to be so casual about it. We need to expect more of each other

and become active members of the current Digital Renaissance in order that our

students have a chance to grow into active creators and innovators who network

professionally and socially as easily as they speak.

If we want measurable results, train

your teachers with an eye on the specific needs and evolution of society. Being an adolescent in the early stages

of the 21st century looks little like the early

stages of the 20th century—when typewriters, the New

England Primer, and paper flourished.

You cannot teach what you have not

made your own. You cannot inspire unless you too are inspired. Quite frankly, the Common Core does

little to inspire any of us, and in the end, may only serve to leave all us

behind.

|

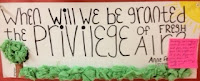

| art by Sarah Louette |

Godless by Pete Hautman

Godless by Pete Hautman